Is Taxi Services An Elastic Or Inelastic

Abstract

This paper investigates the factors that influence the choice of, and hence demand for taxis services, a relatively neglected mode in the urban travel task. Given the importance of positioning preferences for taxi services within the broader set of modal options, we develop a modal choice model for all available modes of transport for trips undertaken by individuals or groups of individuals in a number of market segments. A sample of recent trips in Melbourne in 2012 was used to develop segment-specific mode choice models to obtain direct (and cross) elasticities of interest for cost and service level attributes. Given the nonlinear functional form of the way attributes of interest are included in the modal choice models, a simple set of mean elasticity estimates are not behaviourally meaningful; hence a decision support system is developed to enable the calculation of mean elasticity estimates under specific future service and pricing levels. Some specific direct elasticity estimates are provided as the basis of illustrating the magnitudes of elasticity estimates under likely policy settings.

Access options

Buy single article

Instant access to the full article PDF.

34,95 €

Price includes VAT (Singapore)

Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Notes

- 1.

In recognising that many of the reported elasticities in Table 1 are from studies undertaken quite some time ago, we undertook a search of more recent studies, especially those related to airport access mode. To our surprise and disappointment, we could not build on the earlier evidence. For example the report by Gosling (2008) reviewed many US studies on access mode to the airport and does not report a single elasticity.

- 2.

Hire cars were also considered but the focus of this paper is on taxis.

- 3.

A hire car is a car with a chauffeur. It is not a car that an individual hires from a company such as Avis or Hertz. This was made clear to respondents. As such it is like a taxi.

- 4.

This is equivalent to assuming that individuals first choose the set of relevant alternatives from the universal finite choice set and then conditional of this subset, they chose the most preferred alternative. We, like the majority of studies with variable choice sets, do not model the choice of choice sets from the universal finite set.

- 5.

In cases where respondents had more than three alternative modes of transport available to them for the recent trip used to form the context of the SC experiment, the survey instrument selected as one mode either a taxi or hire car as one alternative in the SC experiment, and two of the remaining alternatives from the set as the last two alternatives in the SC scenario.

- 6.

MPTP gives members half price taxi fares, paying up to $60 per trip. Some members have a yearly limit. The cards cost $16.50 and are valid for 6 years. An individual can become an MPTP member if they live in Victoria, have a severe and permanent disability, and have a disability that means they cannot use public transport by themself. See http://www.taxi.vic.gov.au/passengers/mptp.

- 7.

We were unable to obtain statistically significant parameter estimates for random parameter for this segment, due we suspect to the small sample size.

- 8.

For example, the usual specification in terms of a normal distribution is to define β nk = β k + η k v n where v n is the random variable. The constrained specification would be β nk = β k + β k v n when the standard deviation equals the mean or β nk = β k +hβ k v n when h is the coefficient of variation taking any positive value. We would generally expect h to lie in the 0–1 range since a standard deviation greater than the mean estimate typically results in behaviourally unacceptable parameter estimates.

- 9.

The crowding attribute was simplified in contrast to the trip time reliability attribute that has assigned probabilities of occurrence. In future studies we recommend a similar treatment of crowding as specified for reliability.

- 10.

Although we allowed for the possibility of a recent trip of a heavy downpour, there was very little of this and the majority of respondents indicated it was sunny, overcast or a light rain. We would conjecture that had we a sizeable sample who experienced a downpour on the reported recent trip, we would have identified a statistically significant positive sign for the parameter attached to this attribute level in the context of night travel in particular.

- 11.

The modal constants are important for a number of reasons, none more so than to obtain elasticity estimates. In discrete choice models, elasticities are a function of not just the parameter estimates and the data, but also the choice probabilities and attribute levels. As such, it is important that the mode specific constants reproduce the known market shares, otherwise any elasticities generated from the model will be biased.

- 12.

- 13.

Details of this process are available on request from the authors.

References

-

Basu, D., Maitra, B.: Stated preference approach for valuation of travel time displayed as traffic information on a VMS board. J Urban Plan Dev 136(2), 214–224 (2010)

Article Google Scholar

-

Beesley, M.E.: Competition and Supply in London Taxis. J Transp Econ Policy 13(1), 102–131 (1979)

Google Scholar

-

Bliemer, M.C.J., Rose, J.M.: Experimental design influences on stated choice outputs: an empirical study in air travel choice. Transp. Res. Part A 45(1), 63–79 (2011)

Google Scholar

-

Booz Allen Hamilton: ACT Transport Demand Elasticities Study. Report for Department of Urban Services, ACT, Australia (2003)

Google Scholar

-

Flores-Guri, D.: An economic analysis of regulated taxicab markets. Rev Ind Organ 23(3), 255–266 (2003)

Article Google Scholar

-

Frankena, M.W., Pautler, P.A.: An Economic Analysis of Taxicab Regulation, US Federal Trade Commission, Bureau of Economics Staff Report (1984)

-

Gosling, G.: Airport Ground Access Mode Choice Models: A Synthesis of Airport Practice. Airport Cooperative Research Program Synthesis 5, Transportation Research Board, Washington D.C (2008)

Google Scholar

-

Hensher, D.A., Rose, J.M., Greene, W.H.: Applied Choice Analysis: A Primer. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2005)

Book Google Scholar

-

Louviere, J.J., Hensher, D.A., Swait, J.: Stated Choice Methods: Analysis and Applications in Marketing, Transportation and Environmental Valuation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2000)

Book Google Scholar

-

Queensland Transport (2000) National Competition Policy Review of the Transport Operations (Passenger Transport) Act 1994, Sept 2000

-

Rose, J.M., Bliemer, M.C., Hensher, Collins, A.T.: Designing efficient stated choice experiments in the presence of reference alternatives. Transp. Res. Part B 42(4), 395–406 (2008)

Article Google Scholar

-

Rose, J.M., Bliemer, M.C.J.: Constructing efficient stated choice experimental designs. Transp Rev 29(5), 587–617 (2009)

Article Google Scholar

-

Rose, J.M., Bliemer M.C.J.: Sample size requirements for stated choice experiments. Transportation (Accepted 8 Nov) (2013)

-

Rouwendal, J., Meurs, H., Jorritsma, P.: Deregulation of the Dutch taxi sector. In: Proceedings of Seminar F, European Transport Conference, 37–49 (1998)

-

Schaller, B.: Elasticities for taxicab fares and service availability. Transportation 26(3), 283–297 (1999)

Article Google Scholar

-

Toner, J.P.: The welfare effects of taxicab regulation in English towns. Econ Anal Policy 40(3), 299–312 (2010)

Google Scholar

-

Train, K.E.: Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2009)

Book Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgments

This study was undertaken on behalf of the Victorian Taxi Industry Inquiry and funded by the Victorian Department of Transport. We thank Warwick Davis for all his support during the study. Zheng Li of ITLS undertook a literature review of existing empirical studies on taxi elasticities. The detailed comments of three referees are appreciated.

Appendix A: the decision support system

Appendix A: the decision support system

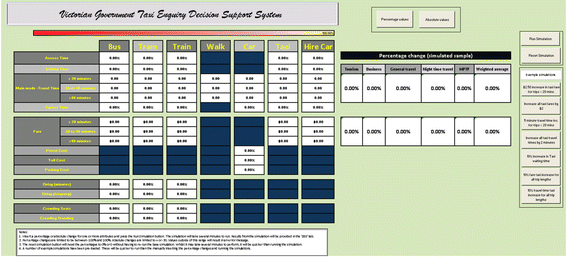

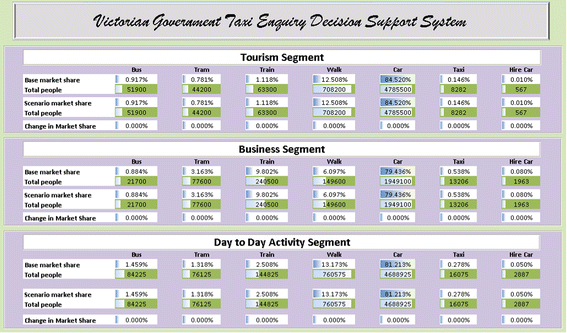

The DSS screens of interest are the input (Fig. 5) and scenario output screens (see Fig. 6). The input screen allows users to enter as either percentage or absolute changes, changes to the attribute levels of the seven modes used as part of this study. For the main in-vehicle or main mode walk times and fares, the DSS has separated the data into trips <20 min, between 20 and 40 min, and >40 min. This allows the user to change as an absolute number, the fares or costs for subsets of the data. For example, the user can change the fare only for trips that are under 20 min, or increase the travel times for trips over 40 min. The DSS also allows for several attributes to be changed at once or only a single attribute to be changed, depending on the specific scenario being tested.

DSS input screen

Full size image

DSS output screen I

Full size image

As shown in Fig. 5, to the right of the scenario section where attribute level changes can be made, are the results of calculations that convert for the taxi mode, the absolute changes for main mode times and fares into percentage changes. For example, if the user wishes to impose a $2.50 increase in taxi fares for trips that are <20 min, the numbers shown in these boxes calculate and show what the percentage change in fares by segment is. Note that the percentage changes will be greater for shorter trips than longer trip lengths, for a given fare change. Two buttons are also available that will switch the main mode or in-vehicle travel times and fares between percentage and absolute value changes.

Not accessible to the user, the DSS makes use of the discrete choice models estimated that are linked to the simulated respondents as discussed above. Given the use of MMNL models for four of the five segments, simulation is required for these models to obtain the predicted market shares. The DSS utilises 1,000 Halton draws per each of the 2,500 respondents to obtain the predicted market shares for a given scenario. As such, each scenario run requires 17,500,000 (2,500 respondents × 1,000 draws × 7 (modes)) calculations per market segment. Given the large number of simulated draws, the running of each scenario is time consuming. Further details of the DSS are available on request.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rose, J.M., Hensher, D.A. Demand for taxi services: new elasticity evidence. Transportation 41, 717–743 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-013-9482-5

Download citation

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-013-9482-5

Keywords

- Taxis

- Elasticities

- Stated choice study

- Decision support system

Is Taxi Services An Elastic Or Inelastic

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11116-013-9482-5

Posted by: lamarchetwoment.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Is Taxi Services An Elastic Or Inelastic"

Post a Comment